STORIES FOR SEEKERS

What Cannot Burn

A Vedantic Parable of Clarity in Dark Times

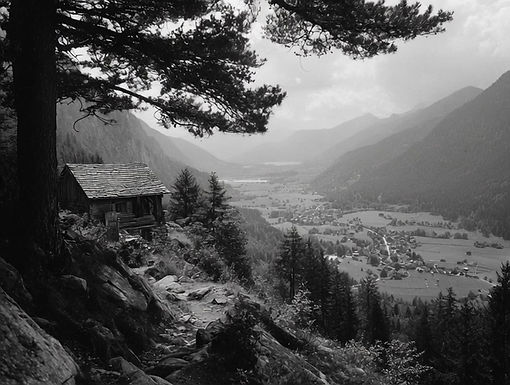

In the shadow of rising fascism, a German sannyasi retreats into the forest—until the world begins knocking at his door. What Cannot Burn is a contemplative story about clarity, compassion, and the quiet fire that ideology cannot touch.

4

The mist came early that morning, thick and low like breath held against the skin of the valley. The world was gray and wet and silent.

Devananda sat near the hearth, the kettle warming, his thoughts nowhere in particular. The letter had not moved from its pouch, but its weight had not left the room.

He was just beginning to rise when the knock came.

Not loud. Three soft taps. Hesitant, like someone unsure if a knock still meant welcome.

He paused. Few ever came to the hut unannounced. Fewer still climbed the trail in mist.

When he opened the door, a girl stood there—perhaps ten years old, wrapped in a threadbare coat two sizes too large. Her cheeks were red from cold. Her dark hair stuck to her face like rain-soaked threads.

She said nothing.

Devananda waited.

After a moment, she reached into her coat and pulled out a cloth bundle. She held it out with both hands.

He took it.

A loaf of bread, still warm. No name. No note.

Just the silence between them—and something unspoken behind her eyes.

He looked at her.

“From the baker’s wife?” he asked gently.

The girl nodded.

“She said to thank you for the herbs. She said you saved her son’s lungs.”

He hadn’t known the boy was her son. He had only given herbs, instructions, and silence.

“Would you like tea?” he asked.

The girl hesitated, then nodded.

Inside, she sat cross-legged on the mat near the fire, hands cupped around the warm clay cup. She didn’t drink right away.

“My uncle says you’re a holy man,” she said after a while.

“I wear these robes,” Devananda replied.

“He also says you’re dangerous.”

Devananda smiled softly. “He may be right.”

The girl frowned. “But you gave us herbs. And you don’t have guns. How can that be dangerous?”

He stirred the fire with a piece of pine branch, watching the sparks spiral upward.

“There are many kinds of danger,” he said. “Some are loud and quick. Some are quiet and slow. Some live in the body. Some live in the mind.”

“Like books?” she asked. “They burned books at the school.”

He looked at her then—not with surprise, but with a kind of sadness he kept beneath the skin.

“Yes,” he said. “Like books.”

“Why?”

He took a breath and let it out slowly.

“Because people are afraid of things that don’t move the way they want.”

She looked down. “Will they burn the people too?”

He didn’t answer right away.

“No,” he said finally. “Not yet.”

When she left, she bowed in the awkward way of a child mimicking what she’s seen adults do. He bowed in return, not as a ritual, but as gratitude—for the bread, and for the question that still burned.

After she disappeared into the mist, Devananda stood outside for a long time, staring into the trees.

A sick child. A loaf of bread, he thought. This is how it begins.

And then, the voice in him whispered again:

If the fire spreads, can you still sit beside it and not reach for a pail?

He returned to the hut and sat. But the silence had changed again.

This time, it wasn’t the letter.

This time, it was the weight of eyes beginning to look to him—not for doctrine, not for miracles, but for the simple question of what one does when the world begins to break.

5

It was near dusk when he heard footsteps—confident ones. Not the shuffle of a villager or the tentative knock of a child.

He opened the door before the man could knock.

“Dieter!” the man beamed, arms wide. “God, look at you. It’s been… what, ten years?”

Devananda blinked. For a moment, he didn’t know whether to speak.

“Mathias,” he said finally. “From the university.”

“The very same,” Mathias said, brushing past him with the ease of someone who had once shared wine and long nights arguing over Kant. “You haven’t aged a day.”

“I’ve aged,” Devananda said, closing the door. “Just differently.”

The man looked around the hut with mild amusement. “So this is the hermitage. I always thought you’d end up in some cave in India.”

“I was in caves. This is warmer.”

Mathias laughed and sat uninvited on the bench by the hearth.

He looked healthy, dressed in a fine wool coat, boots that had barely touched mud. His eyes still carried the same spark—quick, restless—but there was something else now. A tightness. A glint.

“I was in the area for work,” Mathias said. “Thought I’d try my luck. I heard rumors of a ‘German monk’ living in the hills. Figured it had to be you.”

Devananda poured water into the kettle. “What work brings you to a place like this?”

“Consulting. Policy work. I’m advising a regional office now. Educational reform.”

The way he said “reform” made Devananda pause.

Mathias leaned forward. “I read your essay once. The one about detachment and the illusion of self. You always had the soul of a mystic—even when you were still quoting Schopenhauer.”

Devananda smiled faintly. “Some truths don’t need replacing. Only seeing.”

Mathias nodded thoughtfully, then added, “But of course, seeing is a privilege. Not everyone can afford to rise above the world. Some of us have to build it.”

The kettle hissed softly.

Devananda handed him a cup.

There was silence.

Then: “You’re aware, I imagine, of how things are shifting. It’s not like it was.”

“I’ve noticed,” Devananda said.

“There’s fear, yes,” Mathias continued, “but there’s also… opportunity. We’re cleaning house. Making room for strength. Order. Unity.”

The words landed like river stones—smooth on the outside, but meant to sink.

“And this?” Mathias gestured at the hut. “This retreat—how long do you think it will remain safe? Things are tightening. We’re watching for subversive ideas, foreign influences. You wouldn’t want to be mistaken for… something else.”

Devananda said nothing.

Mathias sipped the tea. “You could come back, you know. Speak. Teach. There are people who’d listen now—hungry for meaning. You could frame it well. In alignment with the new vision. You wouldn’t have to hide.”

Devananda looked at him, really looked. Not at the man, but at a kind of impersonal force wearing the man like clothing. The gunas at work.

Not evil. Just twisted. Just dimmed.

“Mathias,” he said softly, “do you remember what we said that night in Dresden, when the rector denied funding to the Jewish scholars?”

Mathias blinked. “I remember shouting.”

“You said, ‘Truth has no uniform.’”

Mathias looked away. “Yes, well. The world has uniforms now. One must adapt.”

He finished his tea, stood, and brushed off invisible dust.

“I should go. The roads aren’t safe after dark. But you—just think about what I said. You still have time to step forward. Before someone decides you’ve stepped aside.”

He placed the cup down with a little too much care.

“It was good to see you, Dieter.”

“I go by Devananda now.”

Mathias paused, smiled faintly.

“Of course you do.”

6

Days passed.

The forest returned to silence.

Devananda spent his mornings splitting wood, his afternoons walking the ridge. He meditated as the sun dipped low, and slept with the fire near his feet.

The letter sat untouched. So did the memory of the girl, and the man from Leipzig.

But silence, as he had learned, is never empty.

He felt it again—before sound came. A presence. Still and waiting.

This time, he opened the door without hesitation.

A boy—no, a man, though not much more—stood hunched beneath a cloak heavy with dew. His hair was matted, a thin line of blood marked one brow. Behind him, the ash trees whispered, almost protectively.

“I’m sorry,” the man said. “I didn’t know where else to go.”

He spoke with a Saxon accent, but the voice was cracked by hunger and exhaustion.

Devananda said nothing. He stepped aside.

The man entered, eyes darting, as if still expecting pursuit. He hovered just inside the door, uncertain whether this sanctuary was real.

“There’s water by the window,” Devananda said, returning to the hearth. “And a blanket in the trunk.”

The man hesitated, then drank. When he sat, he did so with a groan—his ribs must have been bruised. The blanket clung to his shoulders like a confession.

For a while, neither spoke.

Then, quietly, the man said, “They beat me for walking on the wrong road. There’s a curfew now. I didn’t know.”

Devananda looked at him.

“Or maybe they knew who I was,” the man continued, staring at his hands. “My father wrote something once. About the Reichstag fire. They never forgot.”

Silence returned.

Outside, a crow called.

“What do you need?” Devananda asked.

The man swallowed. “Just sleep. One night. I’ll be gone before light.”

Devananda nodded. He stood and poured a little barley into a pot.

The boy watched him. “They say you’re a monk.”

“I am.”

“Not Christian?”

“No.”

“What kind, then?”

Devananda stirred the water. “The kind that watches fire without needing to put it out.”

The boy looked at him, confused. But he said nothing more.

They ate in silence.

When the boy finally curled on the floor, blanket drawn over his head like a burial cloth, Devananda sat again at the hearth.

He did not sleep.

He thought of the ash trees outside—how some lose their leaves late, some early. How some split from lightning but live on.

He thought of the letter. The girl with the bread. The aquaintance from Leipzig.

And now this.

Not a blaze. Just a spark.

But even wildfires begin this way.

He closed his eyes, not to escape—but to see more clearly.

The boy’s breathing deepened. In the quiet, Devananda whispered—not to the boy, but to the dark:

“Let me not confuse stillness with indifference.”