STORIES FOR SEEKERS

What Cannot Burn

A Vedantic Parable of Clarity in Dark Times

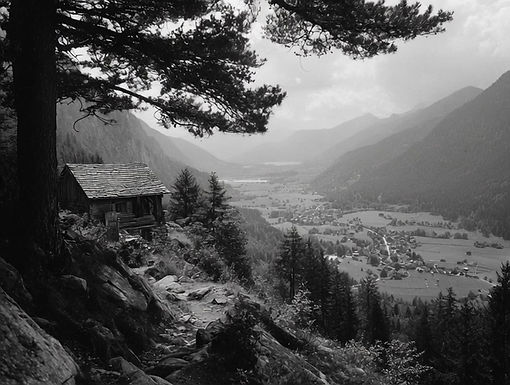

In the shadow of rising fascism, a German sannyasi retreats into the forest—until the world begins knocking at his door. What Cannot Burn is a contemplative story about clarity, compassion, and the quiet fire that ideology cannot touch.

7

The boy was gone by dawn, just as he’d promised. Left behind was the folded blanket, still warm. And a single word carved into the frost on the windowpane:

Danke

Devananda stood before it, unmoving.

Later that morning, he walked to the stream. The air smelled of ash and iron.

Halfway down the slope, a familiar voice startled him.

“You still walk like a monk,” said Frau Elze.

She was older than most, with strong shoulders and the steady gaze of someone who’d outlived every one of her brothers. She had been kind to him when he first arrived, offering a spade for the garden and jars of pickled cabbage in winter. But lately, she had kept her distance.

Today, she looked directly at him.

“Someone saw your lamp last night,” she said. “Said there was movement.”

He waited.

She sighed. “You don’t have to explain. Just know that the road between here and the village is thinner than it used to be. Words travel.”

He nodded.

“They’re looking for anyone who shelters cowards. Or thinkers.” She spat the word like it tasted of rot.

“Is that what he was?” Devananda asked gently.

“I don’t care what he was,” she said. “But they do.”

She shifted her basket to the other hip. “There was a time people kept their heads down. Now they turn each other in for thinking too loudly.”

Devananda watched a hawk circling high above the field.

“They haven’t forgotten who you are,” she added. “A foreign robe, a foreign God.”

“I never brought either,” he said. “Only silence.”

“Doesn’t matter. They’ll hear what they want to hear.”

She softened. “You’ve been good to us. But kindness won’t shield you anymore. I’m telling you this because I don’t want to see you vanish.”

She touched his arm—just once—and turned back toward the village.

Devananda stood there a long while, until the wind shifted and the hawk drifted west.

8

That night, sleep did not come easily.

Devananda lay on his side, listening to the wind comb through the trees like fingers through hair. The hut creaked. Somewhere beyond, a fox screamed like a wounded child. And beneath it all: stillness. Too still.

Eventually, exhaustion overtook thought.

He dreamed of a dry riverbed. He stood barefoot where water should have been. The sky was yellow. The trees were skeletal. A flame burned steadily in his chest—not painful, but bright, like a coal buried deep in ash.

He walked.

Along the banks, he saw villagers—men, women, children—digging at the soil with their hands, mouths parched. They didn’t see him. Their eyes were clouded, as if turned inward. One struck the ground until his knuckles bled, whispering something in a language Devananda could almost understand.

He knelt beside a girl, no older than ten, who had collapsed in the dust. Her skin was cracked like clay. She looked at him and mouthed something.

He leaned closer.

“Is this the world you renounced?” she asked.

He stepped back.

Suddenly, a wall of flame rose between them—silent, hot, impersonal. The child vanished behind it. Then the villagers, one by one, turned toward the fire—not away from it, but into it—walking forward as if drawn by something deeper than fear.

Devananda called out, but his voice made no sound.

Then, another voice came—low, unmistakable, from behind his own eyes:

“You say the fire is not yours. But you were born of it, too.

You do not feed it. You do not flee it.

You sit beside it.

And that, too, is karma.”

He turned and saw no one.

Only the dry riverbed.

And above it, a sky that began to rain—not water, but ash.

He awoke before dawn, sweat clinging to him like a second robe.

Outside, the forest was still.

But the silence no longer felt like sanctuary.

It felt like the moment before a match is struck.

9

The forest was damp that morning, yet something sharp hung in the air.

Devananda stepped outside, kettle in hand, and paused mid-step.

There was smoke—not from his chimney, but thin threads of it rising through the trees beyond the ridge. Not fire. Not yet. But close enough to smell.

He walked the trail slowly, listening.

When he crested the ridge, he saw them: three men in uniform, walking single file along the road that skirted the woods. One carried a lantern, another a rifle, and the third—short, stern-faced—tacked up a paper on a tree with quick, precise movements.

They didn’t look in his direction. But they didn’t need to.

By the time Devananda reached the tree, they were gone.

The paper flapped slightly in the breeze. Its words were brief, large, and unmistakable:

“Sheltering enemies of the state will be treated as treason.”

Below, a list of names. He did not recognize them.

But he didn’t need to.

The message was clear. And it had reached him.

He stood there for a long time. Watching the ink dry.

That evening, he swept the hut, as he always did. He made rice, as he always did. But something had changed. He felt it in his spine—an alertness, a silence no longer sacred but watchful.

After his meal, he lit the oil lamp and sat, facing the window.

He let his hand rest on his knee. The posture was familiar. But the stillness was not.

In his mind, he returned—not to the dream—but to something earlier. A voice in a dusty courtyard in Varanasi. His teacher’s voice, when he was still young and full of zeal:

“The gunas must play, Devananda. Even tamas. Even rajas.

This world does not run on light alone.”

He hadn’t understood then. He had only nodded.

But tonight, sitting in a country far from that courtyard, the words came alive.

“The world exists only because the gunas are allowed to dance.

Deny one, and the play ends.

Even monsters have mothers.”