STORIES FOR SEEKERS

What Cannot Burn

A Vedantic Parable of Clarity in Dark Times

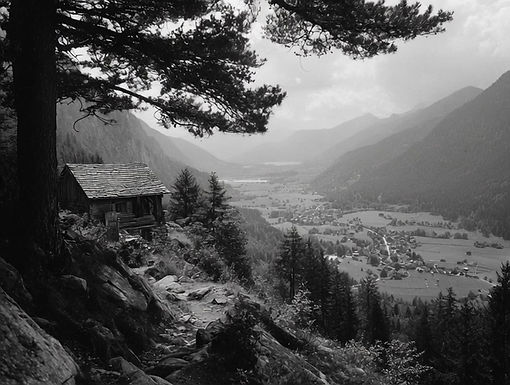

In the shadow of rising fascism, a German sannyasi retreats into the forest—until the world begins knocking at his door. What Cannot Burn is a contemplative story about clarity, compassion, and the quiet fire that ideology cannot touch.

10

It was just after sundown when the knock came.

Not the tentative tap of a child or the panicked pounding of someone pursued. A firm, deliberate knock.

Three times. Then silence.

Devananda stood.

He did not reach for the lamp. He did not call out. He opened the door.

The man who stood there was tall, broad-shouldered, with a long gray coat and a flat cap pulled low. His face was lean, weathered, and marked by a thin scar that ran from his temple to the edge of his mouth. Not fresh. Not old. A scar that spoke of survival, not heroism.

They looked at each other for a long time.

“You don’t know me,” the man said.

Devananda nodded. “But you know me.”

The man glanced over his shoulder, then back. “I was told you don’t ask questions.”

“I try not to,” Devananda said. “But the mind is restless.”

The man stepped inside without being asked.

He removed his coat and sat down without a word. There was something practiced in the way he moved—like someone used to living on the edge of exposure.

They sat in silence for a few minutes.

Then the man spoke.

“There’s a train tomorrow. Midnight. They say it’s the last. After that, the border’s sealed. I don’t want to be on it.”

Devananda didn’t respond.

“I’ve done things,” the man continued. “Things I believed in. Things I don’t. Doesn’t matter now. They’ve turned on me. Called me a traitor.”

He looked up, his eyes dark but clear.

“I’m not asking for shelter. I’m asking what a man should do when he finally sees the machine he built is crushing the wrong people.”

Devananda met his gaze.

“The machine always crushes the wrong people,” he said softly. “Sometimes even the ones who built it.”

The man gave a bitter laugh. “I thought you were a monk. That sounds like politics.”

“It’s not,” Devananda replied. “It’s karma.”

A long silence.

Then the man leaned forward.

“Tell me this,” he said. “If you were me… would you run? Or stay and try to make it right?”

Devananda didn’t answer. He studied the man’s face, the scar, the steady hands, the weight behind his words.

At last, he said, “I’m not you.”

“But you’ve seen what’s coming.”

“Yes.”

“Then help me see it too.”

Devananda looked down at his hands.

They were old hands. Browned by sun, wrinkled by time, steady from years of stillness. Once, he had thought they were no longer of use to the world. But now they trembled—just slightly—with the weight of someone else’s crossroads.

He lifted his eyes.

“You want an answer,” he said. “But you already know what you want to do. You came here to ask if it’s allowed.”

The man frowned.

“I came because I don’t trust myself.”

Devananda nodded slowly.

“That’s a start.”

He stood and poured two cups of water. The clay cups clinked softly. The fire crackled in its stone ring.

“When I first came to the path,” he said, “my teacher told me something I didn’t understand. He said, ‘We renounce action not to avoid it, but to see it clearly.’”

“And can you see clearly now?”

Devananda met his eyes.

“Clear enough to know that clarity doesn’t always bring comfort.”

He sat across from the man.

“You are not here to be forgiven. You’re here to decide what kind of man you want to be, now that your story has cracked open.”

The man shifted. “But what if I choose wrong?”

“Then you live that consequence. And then, if you’re still alive, you choose again.”

He paused.

“This is the world of the gunas. There is no perfect choice. Only a choice made in light or in shadow.”

The man stared into his cup.

“So what would you do?”

Devananda let the silence breathe before answering.

“If I thought I could stop one life from being crushed, I would act. Not to be a savior. Not to make things right. But because compassion does not wait for certainty.”

He added, “But if I acted only to escape guilt, I would be doing it for myself. And that, too, is bondage.”

The man closed his eyes.

When he opened them again, they were different—less frantic, more resolved.

“Thank you,” he said, standing. “I don’t know what I’ll do yet. But I think I know how to listen now.”

He paused at the door.

“You’re not what I expected.”

Devananda smiled faintly. “Neither are you.”

The man vanished into the trees, his coat catching the last light of dusk.

Devananda remained at the threshold for a long time.

In the distance, the wind picked up. Ash trees hissed like old men arguing. The silence did not return. Not fully.

“We are not asked to fix the world,” he whispered. “Only to do what is right when the moment arrives.”

He turned back inside. The lamp flickered. The fire had burned low.

11

The sky cracked open at dawn.

Not with thunder, but with silence too loud to ignore. The birds did not sing. The village bell did not ring. And the mist no longer felt like mist—it felt like smoke.

Something had happened. Or was about to.

Devananda sat in stillness, as he always did. But the stillness no longer mirrored the world. Outside, everything was beginning to shake.

Then, as if drawn from the well of memory, the words returned—spoken long ago in India, beneath a neem tree, when he still believed renunciation meant retreat.

“The gunas are the fabric of the world,” his teacher had said. “Not good and evil. Not gods and devils. Just tamas, rajas, sattva—in endless interplay.”

He remembered how, as a young man, the idea had comforted him.

But now it did not comfort. Now it unveiled.

“The rise of madness is not a glitch in the system,” his teacher had said. “It is the system. Tamas must rise. Rajas must stir. Sattva must hold. If one is suppressed, the others erupt.”

“Even violence?” Devananda had asked.

“Especially violence,” his teacher replied. “It is part of the dream’s rhythm. It comes when the dream forgets itself.”

A knock broke the memory.

A boy this time. Wide-eyed. Breathless.

“They took Herr Braun,” he said. “Just now. From the bakery.”

Devananda’s face didn’t move, but something behind it did.

“Did anyone speak?” he asked.

The boy shook his head. “Everyone watched. No one spoke.”

He nodded. The boy ran off.

Later, seated beneath the bare tree near his hut, Devananda felt the wind shift.

“This is not evil,” he said aloud, not to excuse it, but to see it.

“This is tamas, rising because the world fed it. This is rajas, ignited by fear and hunger. This is the dream turning against itself—because it does not know it’s dreaming.”

“And we—we call it evil, because we are still asleep inside it.”

His eyes closed. The breath slowed. The flame inside held steady.

“To see the gunas is not to escape them. It is to know their dance. And to no longer take their madness personally.”

“The storm is not against me. It is simply a storm.”

In that moment, a sound rose from the village below—shouting, boots, a door slammed open.

Devananda did not rise.

He bowed his head—not in fear, not in defiance, but in deep surrender.

“Let it play,” he whispered.

“Let the dream exhaust itself.”

12

The fire did not come for him.

Not that week. Not the next. The world burned in its own way—names vanished from shop windows, boots echoed in the streets, and eyes learned not to look too long.

But no one came for the man in the hills.

They feared him. Or forgot him. Or perhaps the storm simply passed over, unwilling to disturb something that no longer resisted.

Devananda began to walk again.

Not far. Just to the edge of the trees, where smoke sometimes curled from chimneys that had gone cold, or where mothers whispered bedtime stories with new, tightened endings.

He spoke to no one, but he listened.

He did not teach, but he watched.

He did not interfere, but once, he left a bundle of herbs at a window, unseen.

The girl returned once, months later. Her mother had died. Her father was gone. She came not to speak, but just to sit by his fire.

They did not speak of doctrine. They did not speak of suffering.

Only once, as she looked at the flame, did she ask, “Will it end?”

He answered without turning.

“Everything ends. Except what watches.”

One night, alone again, he sat by the fire and saw it flicker.

It hadn’t gone out. Just flickered.

He felt no dread, no sadness.

“Maya doesn’t end with knowledge,” he thought. “It just stops fooling you.”

The world still trembled. People still vanished. The wind still carried smoke.

But the silence inside him was different now. Not the silence of retreat, but of one who has passed through illusion and come out still.

“This is not a story of good and evil,” he said to the night.

“It is a story of seeing.”

“Of knowing the gunas must move. That violence, too, is part of the wave. That the world will sometimes forget itself—and when it does, it will eat its own children.”

“But even then… something remains. Something watches. Something never touched.”

He touched his chest. Not sentimentally—just an old habit.

“That light,” he whispered, “was never in danger.”

And so he remained.

A man with no country. No mission. No fear.

Only clarity.

Only that which cannot burn.